|

HBO DOCUMENTARY FILMS presents A One Horse Town Productions & Renegade Pictures Co-Production BBC STORYVILLE, ARTE and SWR Supported by GUCCI TRIBECA DOCUMENTARY FUND Supported by a grant from the SUNDANCE Institute Documentary Film Program Supported by World View Broadcast Media Scheme

Directed by Gemma Atwal Produced by Gemma Atwal & Matt Norman Executive Produced by Alan Hayling |

|

Running Time: 98 minutes Shot on HD For further information please contact: For Sales Information please contact:

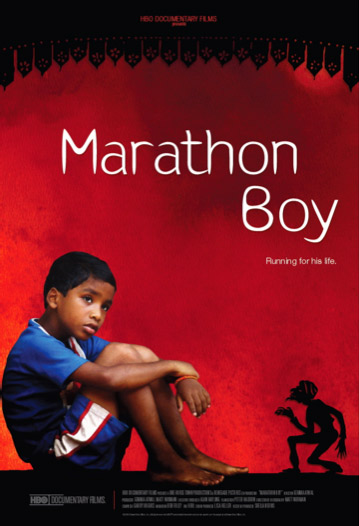

TAGLINEA coach and a slum boy united by a dream, divided by the world.

SHORT SYNOPSISMARATHON BOY is the story of a four-year-old boy who is plucked from the slums of India by his coach and trained to become India's greatest runner, but what starts as a real Slumdog Millionaire turns into the stuff of film noir: a tale of greed, envy and broken dreams.

SYNOPSISGemma Atwal's dynamic epic follows four-year-old Budhia, rescued from poverty by Biranchi Das, a larger-than-life judo coach and operator of an orphanage for slum children in the eastern Indian state of Orissa. When Budhia displays an uncommon talent for long-distance running, Biranchi nurtures his gift, heralding him as a folk hero for the impoverished masses, and maybe even for India itself. But after golden child Budhia breaks down during a world-record 65 kilometer run at the age of four, public opinion begins to turn on the guru and his disciple, and soon the two are swept up in a maelstrom of media controversy and political scandal.

Following Budhia's roller-coaster journey over five years, Marathon Boy is a Dickensian tale of greed, corruption, and broken dreams set between the heart-racing world of marathon running, the poverty-stricken slums, and the political intrigue of a modernizing India. Nothing is what it seems in Budhia and Biranchi's riveting story, and Atwal continually shifts viewer identification to tell both a shocking story of opportunism and exploitation, but also a touching portrait of an authentic bond between a parent and child.

“MARATHON BOY” – FILM SYNOPSIS

Budhia Singh’s life reads like a Bollywood movie scripted by Dickens. Born in India, next to a railway track, abused and beaten by an alcoholic father, he is sold at the age of three by his impoverished mother to a street hawker. Destined to lead a desperate existence as a beggar, Budhia is then rescued by a concerned local judo coach, who runs an orphanage for slum children. It doesn’t take long for Budhia to reveal his remarkable talent for running. Biranchi seizes the opportunity to do something much more symbolic for India’s poor, as he has done so many times for other slum children in the judo arena. He embarks on a mission to turn Budhia into a running phenomenon. Within six months, Budhia has run twenty half- marathons. Within a year, he has run 48 full marathons. What makes this achievement even more remarkable is that Budhia is still only four years old. He’s become the darling of the masses, an Indian icon, and is mobbed everywhere he goes. Now Biranchi is convinced that he has the potential to become India’s greatest runner and first Olympic marathon champion. But with the fame comes the controversies. At the end of his record-breaking 65 km run, he collapses. With the world’s eyes on them and an international storm brewing, the Indian government decide to intervene, accusing the coach of cruelty, and threatening to take his newly- adopted son into care. Is Biranchi effectively enslaving the boy for his own gain? Has Budhia merely traded slum squalor for sporting slavery? Or is Biranchi the man who saved Budhia from a desperate future, a man who loves Budhia as his own son? Even though they still don’t make trainers his size, an opportunistic tug of war is played-out by adults over Budhia’s control. He is caught in the crossfire of lawyers and politicians. Biranchi openly mocks his detractors while inviting the state government to his judo hall to see the food and shelter he provides for Budhia. He gathers all the slum children to protest outside the Child Welfare Committee, holding banners saying "What about us?" Biranchi relishes being a spokesman for the poor, lambasting the Government for their hypocrisy. The Media are whipped into a frenzy - headline stories and publicity strategies in both camps fuel the controversy. In the midst of this furore, the biological mother who sold her only son to a stranger for $10, and who has for so long championed Biranchi as a saviour, dramatically changes tact. She accuses the coach of torturing her son. Biranchi is thrown into jail. Budhia is kidnapped by his mother; forced back into the slums as she demands her share of the spoils from her son’s achievements. Budhia is effectively held ransom, unable to see the adoptive father he loves, the debate and intrigue entirely beyond his control. Without his son, Biranchi is a broken man. For the first time he ponders whether to go on fighting or to abandon the struggle which has brought him to the brink of a nervous break-down. He pours scorn on the accusation of torture and the perception that he is gaining financially out of the boy. He claims that the Minister for Child Welfare bribed Budhia’s mother to make the charge and that the government wants control over Budhia, and a piece of his reflected glory. Biranchi is acquitted of all charges. But before any solutions regarding the fate of Budhia can be found, a shocking event takes place. Biranchi is murdered by a gangster, shot with three bullets at point- blank range in a slum ‘mafia’ killing. Budhia is woken-up in the middle of the night and is told the news by journalists. He falls silent, speaking only to tell the endless stream of reporters: “no more questions”. His life has come full circle and, not for the first time, his survival hangs in the balance. For the world, Budhia has been spared his enslaver but for this small boy, he has lost his mentor and father-figure, the only loving advocate he ever had. Who killed coach Biranchi Das - what precisely was the motive? And what becomes of Budhia Singh, India’s ‘wonder boy’, the world’s youngest marathon runner? As the investigation into the killing unfolds, Budhia is once again rescued from his humble beginnings and awarded a scholarship for sporting excellence from the very state government who claimed his running was tantamount to torture.

CRITICS“Ripe for a fiction remake, "Marathon Boy" is the fantastical yet factual story of foul-mouthed Indian slum child-turned-marathon runner Budhia Singh. A tale that would have been a sordid curiosity in lesser hands than those of helmer Gemma Atwal, the docu transcends its tabloid origins to become something epic, artistic and even archetypal. HBO, in its not uncustomary wisdom, has secured broadcast rights, but the pic's cinematic virtues deserve a bigscreen, and its true-crime qualities could fill arthouse seats. That Atwal tells the story in real time, with extraordinary access to all the principals, simply makes a good story better. Singh, 3 years old when his slum-dwelling mother sells him to an abusive peddler, is rescued by judo instructor Biranchi Das and brought to live at Das' self-styled sports center and orphanage, Judo House. There, with his wife, Gita, and their loose family of salvaged children and athletes, Das trains India's better judo competitors, scrambling to support his ever-expanding number of dependents. As Singh himself explains, he was once ordered by Das to run as punishment for his filthy language. He started at 6 a.m., and when Das returned home at 1 p.m., Singh was still running. Knowing he had some kind of prodigy on his hands, Das began training the boy, and before Singh was 5, he had run 48 full marathons and become the toast of Orissa, the state whose authority would eventually come down on both their heads. Is Das only in it for the money? One of the film's central questions is: what money? Although Singh is fast becoming a sensation, Das' profit motive is hard to locate; he seems to be in it for the glory that would come to both him and India, should he actually cultivate an Olympic marathon runner. The attention he and Singh attract includes that of child welfare officials in Orissa, who can't quite put their finger on what Das is doing wrong but accuse him of exploitation. Das reacts with vitriol, questioning their authority and defying their orders; Singh is banned from running, spurring Das to look for loopholes. Hostilities escalate, and the entire nation becomes engrossed in the adventures of the short long-distance runner. With no narration and very few subtitles, Atwal lets the story mostly tell itself; the several animated sequences, done in Raj-era shadow-puppet style, are a charming adornment. With a few exceptions, the helmer also sticks to her own footage. The fact that she was in on the story so early not only gives the docu a sense of immediacy and drama, but also the proper journalistic bonafides: Singh's biological mother, who will later accuse Das of all manner of crimes against her son, testifies to the judo instructor's virtues and goodness early in the film -- something that will come back to indict her later, at least in the minds of viewers. Atwal and her d.p./co-producer, Matt Norman, seem to get to everyone, from child-welfare bureaucrat R.S. Mishra (who seems far less outraged about Singh's well-being than about Das' defiance) to the slum cronies of Singh's mother. Singh himself seems like a trainwreck: While Das' motives may not be malicious, he's a gifted hustler of the media, and the boy is obviously parroting his trainer's words when he's being interviewed. This is nothing, however, compared to what others coerce Singh into saying, as "Marathon Boy" moves away from the worlds of sports and petty politics and crosses the line into top-level corruption, assassination and grief. Production values are tops, including some glorious visuals by Norman.” John Anderson – Variety

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“The tale about an Indian boy with the gift of nearly superhuman athletic endurance, which British journalist Gemma Atwal chronicles over five years in this unforgettable documentary, rivals any dramatic thriller. The story was an oddity, the kind of thing one reads in a “weird but true” news column: a 3-year-old boy in India’s eastern state of Orissa is discovered to have the gift of nearly superhuman athletic endurance. Little Budhia Singh - born in a Bhubaneswar slum and sold by his mother to a street hawker -- is rescued by a local sports trainer and impresario who discovers that the boy can run. And run, and run. By age 4, Budhia has already completed in a stunning 48 full marathons, and he becomes the world’s youngest marathon runner when he makes the Limca Book of Records with a run of 40 miles in just over seven hours. British journalist Gemma Atwal was transfixed when she spotted Budhia on a BBC news site in 2005. She decided to track down Budhia and the trainer who made it all possible, Biranchi Das. The tale she chronicles over the next five years in this unforgettable documentary rivals any dramatic thriller. Marathon Boy is blessed with two unforgettable central characters, and exposes layers of political intrigue, greed and even a brutal murder, while raising questions about the nature of exploitation. Screened in documentary competition at the San Francisco International Film Festival, the film will air exclusively on HBO. Although Marathon Boy is named after young Budhia, the real star that emerges is Das, a handsome, charismatic and P.R.-savvy judo trainer whose students have gone on to represent India in the Olympics. Das knew that Budhia had something special, and was ready to go to any length to push him to achieve his extreme feats. Das and his wife adopt the boy so that he can train him. Das feeds him, clothes him, sends him to school and offers him fame and the approval of millions. Budhia seems to thrive, but concerned Indian child welfare agencies and local government officials distrust his mentor’s motives, and throw up resistance and bureaucratic roadblocks. Budhia’s supporters can’t see why the wrath of the law is focused on Das. “Kids from the slums are working in brick factories, dying in the streets, yet no one cares for them,” says one character in the film. But shocking images of the slim child, soaked in sweat and dangerously dehydrated after the record-breaking 40-mile run in 93-degree heat, tell another story. Atwal says she had a strict policy not to intervene, but she was so disturbed filming these scenes that she switched off the camera and, in tears, started screaming for help. The film’s derivative soundtrack is its only weak link. But Atwal, a journalist making her feature documentary debut, has created a remarkable film that poses disturbing questions. Her clever use of shadow puppet animation between scenes lends the film the air of a grim fairy tale. The Bottom Line: Documentary about world’s youngest marathon runner tells a riveting and at times heartbreaking story about ambition, greed and resilience.” Lisa Tsering - The Hollywood Reporter (San Francisco Int’l Film Festival)

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“A hero’s journey so ripe for the making of myth that Joseph Campbell would be proud, and culminates in tragedy so Shakespearian it’s hard to believe he didn’t write it. All the more astonishing given Marathon Boy is not fiction, but a documentary. The fictional familiarities do not end there – born into a slum in the eastern Indian state of Orissa, Budhia Singh (the Marathon Boy of the title) eventually finds his way out through glory, adulation and potential riches (Slumdog Millionaire?) after being sold and resold until his athletic abilities and tenacity catch the eye of someone who knows how to apply them (Gladiator?) – Biranchi Das, a judo teacher who also runs an orphanage. Boy and coach, or Wonder Kid and Guru as they describe themselves, train hard for a series of ever-increasing physical challenges (Rocky? The Karate Kid? every boxing or sports film ever made?!) until Budhia runs a staggering 42 miles in around seven hours and sparks debate – is Biranchi Das a provider of opportunity or an exploiter of children? – which attracts government and gangster involvement with tragic consequences. That the shadow of so many archetypes, from such staples of modern fictional film, can be sensed hovering throughout Marathon Boy is a credit to the storytelling abilities and sheer enduring commitment of director Gemma Atwal (who perhaps deserves the moniker Marathon Girl). She forges an almost impenetrable story arc using footage gathered over several years (that begins with Budhia aged three, and ends when he’s aged eight) from subjects whose twists, turns, complexities and ultimate fates would have been impossible to predict at the outset, and perhaps even during the first few years of filming. What elevates the film, and Atwal, to the fringes of mastery is a refusal to follow the more hyperbolic path through, and around, the events as they play out. Instead, the frisson surrounding the controversies at the centre of the film, and their obvious potential for high drama, is tempered with differing perspectives that introduce the concepts of unreliable narrator and objective versus subjective truth. This provides the necessary seeds of doubt to engage the audience whilst making room for a broader meditation on the power of the media (Budhia’s mother, at one point, proclaims “I saw it myself on TV!” as proof of her beliefs) and the dominance of celebrity. Marathon Boy operates successfully on a number of levels – as myth vérité and high tragedy, as rags to riches morality tale and, of course, compelling documentary. If it did happen to be a superhero film, no doubt this would be the beginning of a fruitful franchise.” Matt Strachan – Documentary Film-makers’ Group (DFG)

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“The film never moves into the space of a neatly packaged story. Instead it seeks to capture the ambiguity and complexity driving each characters’ desire to own and care for this exceptional young and talented boy.” IDFA Special Jury who nominated the film into the “Top 3 Feature Documentaries 2010” ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“Stop right there. Don't Google "Marathon Boy." Don't Google "Budhia Singh" and for Godssakes don't even type "Biranchi Das" into your search bar lest you ruin one of the strangest, most provocative and debatable documentaries in recent memory. Director Gemma Atwal spent five years following the complex relationship between Budhia, the Slumdog Prefontaine who became the most famous toddler in India by running six half-marathons by the age of four, and his foster father Biranchi, the trainer-turned-national controversy. What begins as a heartwarmer of a story about a precocious boy plucked out of the slums to become a national icon takes a slow turn into troublesome territory as Budhia is pushed into performing increasingly radical runs in front of thousands of admirers lining the streets and hordes of media cameras, all lassoed in by Biranchi, a born PR wizard embraced by the people as an inspiration and labeled by the government's child welfare agencies as a possible child exploiter. Atwal does an admirable job of constructing a colorful think-piece out of complex questions about objective versus subjective truths, questionable intentions, media's influence and the nature of poverty in the slums of India. More so, the director should be applauded for providing a removed, impartial take on the hotly-debated wonderboy, provoking questions and, thankfully, never once editorializing. The movie's wild and the ending is a top-tier shocker. But the conversations after the lights come up are great. Just stay away from Google.”

John Tarpley - Arkansas Times

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“This amazing story of a slumdog boy who inspires the Indian state of Orissa with his record-breaking marathon at the age of four is just plain riveting. What happens after the running is what makes the tale so intriguing, and disturbing. With a corrupt state government and criminal slumlords all accusing his caregiver of profiteering, young Bhudia becomes the focal point of a heated dispute that leads to a shocking end. One of the best docs I've seen this year.”

Tim Basham – Paste Magazine Q&A WITH DIRECTOR GEMMA ATWAL

How did you first hear about Budhia Singh and why did you decide to make a film about him? Given Budhia’s age at the time and the intensity of controversy surrounding his situation, what was it like to balance the impulse to “observe” vs. “intervene” in your role as a documentary filmmaker? You followed Budhia and the drama that ensued his success as a marathoner for five years, that’s over half of his lifetime. How did your relationship with Budhia and his confidents evolve over the process and how did it affect, if at all, your approach to the story? As I spent more time in India with Budhia and Biranchi, I also shifted my approach to the story to a more Indian perspective (I'm part Indian myself). Set in the Indian context, this wasn't a simple story of child exploitation, it's a story grounded in hope, the hope of a guru and a disciple who could go all the way to fulfil a dream for India. What adds to this richness is that the dream is inherently flawed and problematic, and Biranchi Das is not our hero, he's the anti-hero, a deeply flawed lead character. This shift was important to me, because it added elements of hope versus broken dreams, tragedy versus triumph. Why did you decide to incorporate stop motion animation in the film? What were some of the most challenging and rewarding aspects about making this film? The other challenge for me involved a decisive turning point in the film whereby Budhia's birth mother, Sukanti, whom I came to know very well, declares her discontent with Biranchi Das and it sets off a chain of devastating events. This was tough filming, because it's difficult to watch individuals you care about fighting between themselves and not do anything, especially when a small boy is caught in the crossfire. Privately, I would spend a lot of time chatting with Biranchi and Sukanti about what was happening, and ultimately you can only empathise and understand how they both feel, and document that, without taking sides. By far the most rewarding aspect is having met Budhia and the other slum children whom Biranchi rescued from a life of great social misery, each with their own exceptional story to tell of resilience and survival against the odds. And to see Budhia having come through, having survived all the adults fighting to control him. I think in that final interview with him, we found his voice: that of a conflicted but exceptional 9-year-old-boy, who just wants to fit in.

ABOUT THE FILMMAKERS

Gemma Atwal – Producer & Director

Prior to documentary work, Gemma spent four years working as a journalist in Africa, South-East Asia and Europe for the NOA Media Group of Companies in Madrid. She also gained experience in radio broadcasting, initially training through the BBC and later working for Nigerian State Radio as an on-air reporter. Gemma has an MSc (Distinction) in International Human Rights Law and a Double First Class Honours degree in Literature & Politics. Gemma is co-partner in One Horse Town Productions. This is her first feature documentary.

Matt Norman – Producer & DOP

Documentary credits include: Planet Earth “Pole to Pole” - BBC (Winner Best Cinematography Non-Fiction: EMMY/ RTS / BAFTA/ Jackson Hole), Amazon with Bruce Parry - BBC/ Discovery (BAFTA nominated for best Factual Photography), “Going Tribal” - BBC (BAFTA nominated). Matt is one of the principle documentary cameramen on the BBC’s “Human Planet” (2011 BAFTA Winner Best Factual Photography), the landmark follow-up to “Planet Earth”.

Alan Hayling – Executive Producer

“MARATHON BOY” - FILM CREDITS & TECHNICAL INFO |

|

Director |

GEMMA ATWAL |

|

Producers |

GEMMA ATWAL |

|

Executive Producer |

ALAN HAYLING |

|

Film Editor |

PETER HADDON |

|

Director of Photography |

MATT NORMAN |

|

Composer |

GARRY HUGHES |

|

Animation |

BEN FOLEY |

|

Additional Photography |

TONY MILLER |

|

Production Sound |

AJAY BEDI |

|

Online Editor |

ALEXIS MOFFATT |

|

Colorist |

JAMES CAWTE |

|

Dubbing Mixer |

RICHARD LAMBERT |

|

Dubbing Editors |

IAN BOWN |

|

Post Production Facility |

FILMS AT 59 |

|

Film Archive |

AAJ TAK |

|

LIMITED News Archive |

TIMES OF INDIA |

|

Translators |

SATYA SHIV MISHRA |

|

Special Thanks to |

PETER SYMES |

|

In Memory Of |

KAMAL PAREEK |

|

Head of Production, One Horse Town Productions |

KAMAL PAREEK |

|

Head of Production, Renegade Pictures |

MARIA LIVESEY |

|

Assistant Producer |

PURUSOTTAM SINGH THAKUR |

|

Production Manager |

MIRANDA DURRANT |

|

Production Accountant |

NUALA MCLAUGHLIN |

|

Co-Executive Producer, BBC Storyville |

GREG SANDERSON |

|

Co-Executive Producer, Gucci Tribeca Documentary Fund |

RYAN HARRINGTON |

|

Co-Executive Producer, Touch Productions |

MALCOLM BRINKWORTH |

|

Commissioning Editor, BBC Storyville |

NICK FRASER |

|

Commissioning Editor, SWR |

MARTINA ZÖLLNER |

|

For Home Box Office: Senior Producer |

LISA HELLER |

|

For Home Box Office: Executive Producer |

SHEILA NEVINS |

This

film was supported by the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program

A

co-production with ARTE in co-operation with SWR

In association with

BBC Storyville

In association with Touch Productions

Supported by

World View Broadcast Media Scheme

Supported by Tribeca Film Institute

A

One Horse Town Productions & Renegade Pictures Co-Production

Home

Box Office

Copyright 2010 Renegade Pictures (UK) Ltd and One Horse Town Productions Ltd. All Rights Reserved

Technical information: DVCPRO HD 1080i/25P, 16:9 / Camera: Panasonic HDX900

|